Git Installation Guide Install Git -On Ubuntu Step1 : Update apt repository. apt-get update Step2 : Install git apt...

Git Installation Guide

Install Git -On Ubuntu

apt-get update

apt install git -y

Install Git -On CentOS/RedHat OS

yum update -y

yum install git -y

Why Version Control is required

Issue Without Version Control System

With Version Control system

Version Control System

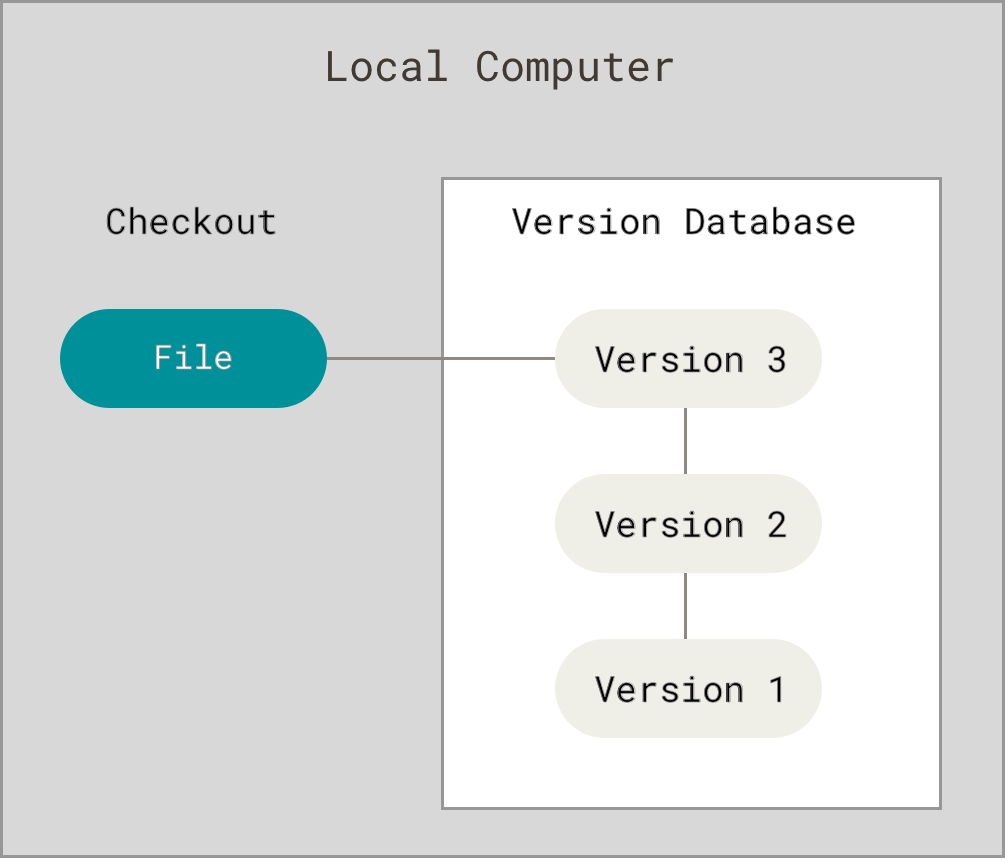

Local Version Control Systems

Many people’s version-control method of choice is to copy files into another directory (perhaps a time-stamped directory, if they’re clever). This approach is very common because it is so simple, but it is also incredibly error prone. It is easy to forget which directory you’re in and accidentally write to the wrong file or copy over files you don’t mean to.

To deal with this issue, programmers long ago developed local VCSs that had a simple database that kept all the changes to files under revision control.

One of the most popular VCS tools was a system called RCS, which is still distributed with many computers today. RCS works by keeping patch sets (that is, the differences between files) in a special format on disk; it can then re-create what any file looked like at any point in time by adding up all the patches.

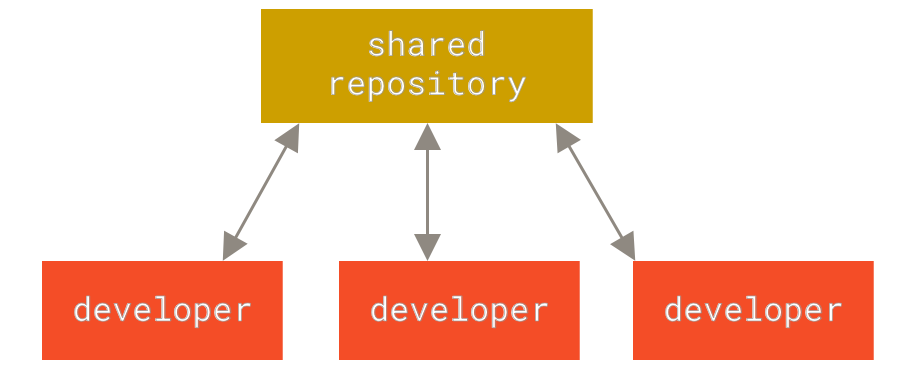

Centralized Version Control Systems

The next major issue that people encounter is that they need to collaborate with developers on other systems. To deal with this problem, Centralized Version Control Systems (CVCSs) were developed. These systems (such as CVS, Subversion, and Perforce) have a single server that contains all the versioned files, and a number of clients that check out files from that central place. For many years, this has been the standard for version control.

This setup offers many advantages, especially over local VCSs. For example, everyone knows to a certain degree what everyone else on the project is doing. Administrators have fine-grained control over who can do what, and it’s far easier to administer a CVCS than it is to deal with local databases on every client.

However, this setup also has some serious downsides. The most obvious is the single point of failure that the centralized server represents. If that server goes down for an hour, then during that hour nobody can collaborate at all or save versioned changes to anything they’re working on. If the hard disk the central database is on becomes corrupted, and proper backups haven’t been kept, you lose absolutely everything — the entire history of the project except whatever single snapshots people happen to have on their local machines. Local VCS systems suffer from this same problem — whenever you have the entire history of the project in a single place, you risk losing everything.

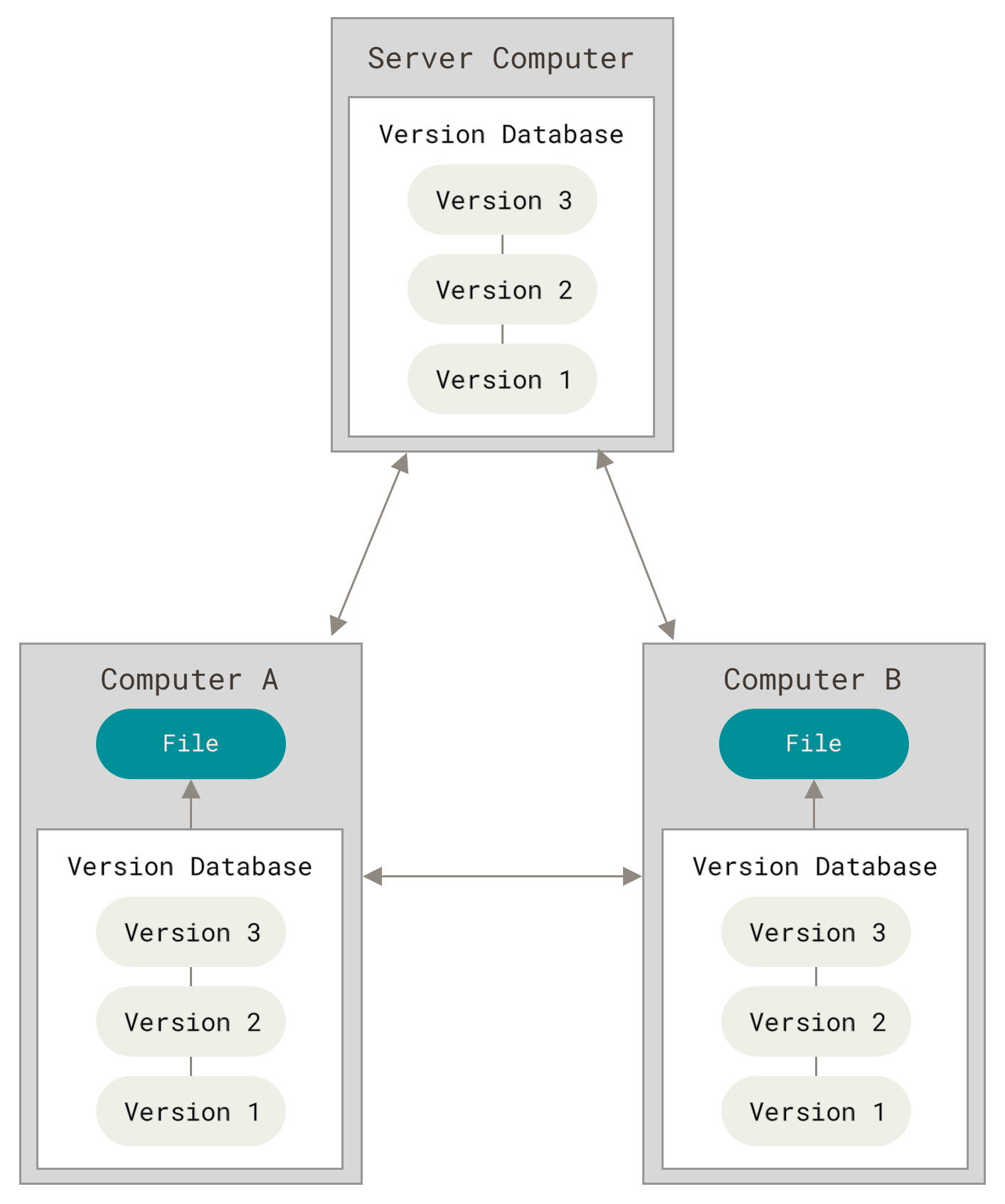

Distributed Version Control Systems

This is where Distributed Version Control Systems (DVCSs) step in. In a DVCS (such as Git, Mercurial, Bazaar or Darcs), clients don’t just check out the latest snapshot of the files; rather, they fully mirror the repository, including its full history. Thus, if any server dies, and these systems were collaborating via that server, any of the client repositories can be copied back up to the server to restore it. Every clone is really a full backup of all the data.

Furthermore, many of these systems deal pretty well with having several remote repositories they can work with, so you can collaborate with different groups of people in different ways simultaneously within the same project. This allows you to set up several types of workflows that aren’t possible in centralized systems, such as hierarchical models.

What is Git

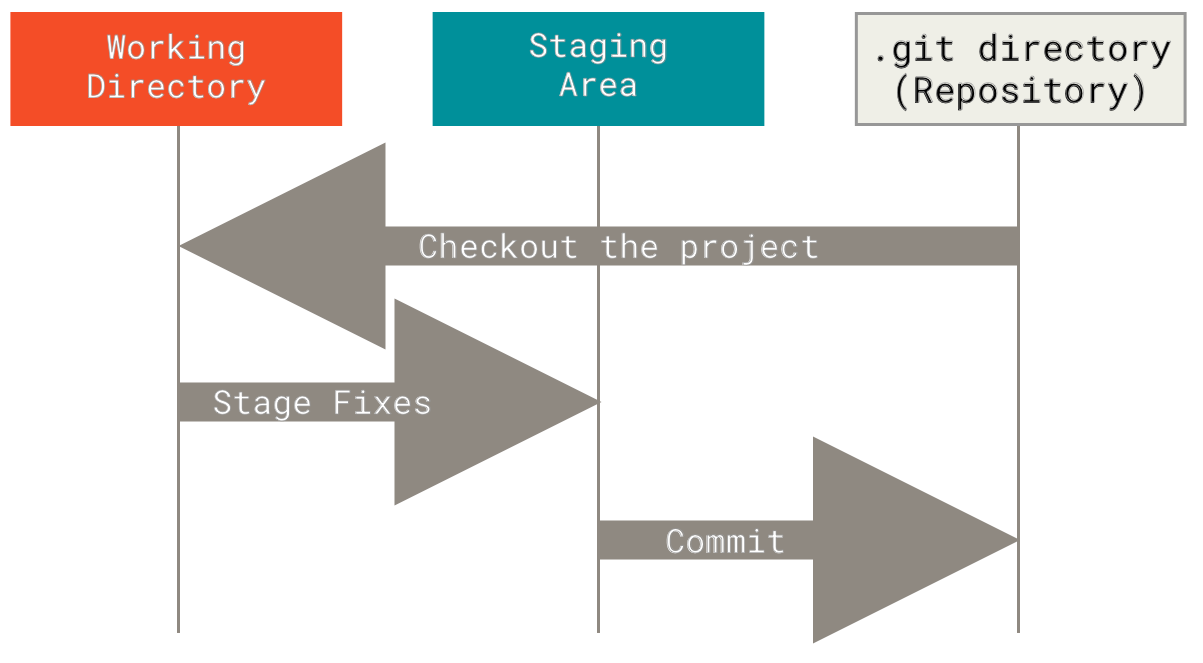

The Three States(Git Work Flow)

Pay attention now — here is the main thing to remember about Git if you want the rest of your learning process to go smoothly. Git has three main states that your files can reside in: modified, staged, and committed:

Modified means that you have changed the file but have not committed it to your database yet.

Staged means that you have marked a modified file in its current version to go into your next commit snapshot.

Committed means that the data is safely stored in your local database.

This leads us to the three main sections of a Git project: the working tree, the staging area, and the Git directory.

The working tree is a single checkout of one version of the project. These files are pulled out of the compressed database in the Git directory and placed on disk for you to use or modify.

The staging area is a file, generally contained in your Git directory, that stores information about what will go into your next commit. Its technical name in Git parlance is the “index”, but the phrase “staging area” works just as well.

The Git directory is where Git stores the metadata and object database for your project. This is the most important part of Git, and it is what is copied when you clone a repository from another computer.

The basic Git workflow goes something like this:

You modify files in your working tree.

You selectively stage just those changes you want to be part of your next commit, which adds only those changes to the staging area.

You do a commit, which takes the files as they are in the staging area and stores that snapshot permanently to your Git directory.

If a particular version of a file is in the Git directory, it’s considered committed. If it has been modified and was added to the staging area, it is staged. And if it was changed since it was checked out but has not been staged, it is modified.

Raman is a user and he wants to set his username and email address for git commit.

$ git config --global user.name "raman"

$ git config --global user.email raman@example.comRaman is working on a new project called "my_project" and he wants to maintain all the changes to the code on his local system.

$ mkdir /home/ubuntu/my_project$ cd /home/ubuntu/my_project$ git init$ ls -laLet's first create some files in "my_project" dir

$ touch 1.txt 2.txt 3.txt 4.txt$ git add 1.txt$ git status$ git commit -m " 1.txt" is added$ git status

$ git add .

$ git status

$ git commit -m " 2.txt, 3.txt, 4.txt files are added"

Remove file 1.txt from git repository and delete it permanently

$ git rm 1.txt$ git reset --hardAdd a new file 5.txt to my_project directory and add to Staging and then remove it from staging and move back to untracked list

$ touch 5.txt$ git add 5.txt$ git status$ git rm --cached 5.txt$ git statusRaman wants to ignore some exe files to be the part of version control system.

$ git log$ git log --amend$ git tag <<version number>>$ git remote add origin <<url>>$ git push origin master$ git push origin --tags$ git clone <<url>>$ git pull origin master

COMMENTS